I came upon 2 studies recently which really piqued my interest immediately. The suggestion by many patients that the mobile “lump”/nodule in their lower back is “causing” their trouble is VERY common in my experience. These two commentaries point out that in fact the patient may not just be imagining that the proximity of the lump to their pain isn’t coincidence…the nodule may well be the source. I have encountered several notable cases of this over the last 28 years, but recently had a post-surgical patient absolutely convinced that “the damn lump in my back is giving me the pain!”…”but no one will believe me”. After probing the area it became apparent that it wasn’t just an “overlaying” lump (common with many lipomas which are not a pain source), this lump appeared to be the actual source of the pain. the pain interestingly enough was a “discal” like pain but with nebulous motion-findings. The lump was injected, pain relief was dramatic and it was removed. And the patient was extremely satisfied with the outcome.

Aqri 2013;25(2):83-6. doi: 10.5505/agri.2013.63626.

[Episacral lipoma: a treatable cause of low back pain].

[Article in Turkish]

Erdem HR1, Nacır B, Özeri Z, Karagöz A.

Abstract

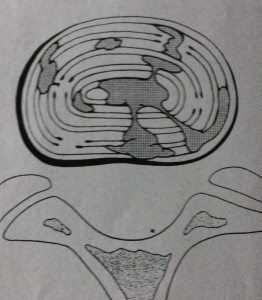

Episacral lipoma is a small, tender subcutaneous nodule primarily occurring over the posterior iliac crest. Episacral lipoma is a significant and treatable cause of acute and chronic low back pain. Episacral lipoma occurs as a result of tears in the thoracodorsal fascia and subsequent herniation of a portion of the underlying dorsal fat pad through the tear. This clinical entity is common, and recognition is simple. The presence of a painful nodule with disappearance of pain after injection with anaesthetic, is diagnostic. Medication and physical therapy may not be effective. Local injection of the nodule with a solution of anaesthetic and steroid is effective in treating the episacral lipoma. Here we describe 2 patients with painful nodules over the posterior iliac crest. One patient complained of severe lower back pain radiating to the left lower extremity and this patient subsequently underwent disc operation. The other patient had been treated for greater trochanteric pain syndrome. In both patients, symptoms appeared to be relieved by local injection of anaesthetic and steroid. Episacral lipoma should be considered during diagnostic workup and in differential diagnosis of acute and chronic low back pain. 2000 Apr;49(4):345-8.

Fibro-fatty nodules and low back pain. The back mouse masquerade.

Curtis P1, Gibbons G

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Few useful interventions exist for patients with persistent low back pain. We suggest that a fibro-fatty nodule (“back mouse”) may be an identifiable and treatable cause of this and other types of pain.

METHODS:

We describe 2 patients with painful nodules in the lower back and lateral iliac crest areas. In both cases, the signs and symptoms were unusual and presented at locations distant from the nodule. One patient complained of severe acute lower abdominal pain, and the other had been treated for chronic recurrent trochanteric bursitis for several years.

RESULTS:

In both patients, symptoms appeared to be relieved by multiple injection of the nodule.

DISCUSSION:

There is agreement that back mice exist. Referred pain from the nodules might explain the distant symptoms and signs in these cases. Multiple puncture may be an effective treatment because it lessens the tension of a fibro-fatty nodule.

CONCLUSIONS:

Randomized trials on this subject are needed. In the meantime, physicians should keep back mice in mind when presented with atypical and unaccountable symptoms in the lower abdomen, inguinal region, or legs.